Imagine how great it would be if all the industry’s players made a thorough commitment to traditional three-step distribution. Suppose they raised the equivalent of millions of dollars a year to promote the industry, and saw to it that thousands of contractors received top-notch training and personal assistance in accounting, finance, salesmanship, advertising, merchandising and every other facet of business education. What if the industry’s largest trade association had twice as many members? What if the government worked hand-in-hand with industry leaders to make it easier to do business? What if there was so much work available that your main concern was finding enough people to handle it all?

A hopelessly utopian vision, you say? Nope. This is pretty much the way the plumbing-heating industry operated during the 1920s.

Fresh from victory in "the war to end all wars," America rode a wave of optimism and prosperity unlike any seen before or since. The United States of 1920 had but 5 percent of the earth’s population, but was producing 24 percent of the planet’s agriculture, 40 percent of its minerals and 35 percent of manufactured goods. Our GNP of $225 billion was almost three times as great as England, our closest competitor. We had a $5 billion trade surplus and half of all the gold in the world. U.S. bank deposits surpassed those of all other banks in the world combined, with billions to spare. Yet there was no inflation. Prices of manufactured goods were actually declining, making more and more modern conveniences affordable to more and more people. "It is impossible for things to go wrong," declared a bank executive in a speech that cited these statistics.

Check out this giddy description penned in 1920 by Henry Gombers, long-time staff chief of the Heating and Piping Contractors National Association, now MCAA:

"As a nation we are out of tune with the infinite. It may be that our national life never vibrated in exactly the same key. Or perhaps the harmony of the spheres has changed from the sweet music of the ancients to the clanging, clattering, ear-splitting noises of a ‘cow-town’ on circus day ...

"The past year has been our circus day. What a wonderful ‘fling’ we have had! We have lived on the top of the world. Nothing has been too good for us. We have thrown our money around in true cowboy style. We have hooted and yelled and let our shooting irons bark on the slightest occasions," wrote Gombers.

In It Together

National prosperity gave most industries a boost. Another driving force for the plumbing-heating industry was a movement known as "trade extension." It was a concept borrowed from an organization called the National Dealer Service Association, which represented manufacturers and wholesalers in various retail industries.This was an era before TV and radio. Whatever passed for "mass marketing" had to be channeled through slow and inefficient print media. Big merchandising businesses concluded that better results could be achieved by helping retail dealers advertise in local markets. Left to their own devices, retailers were not apt to do much advertising, and what little they did tended to promote themselves rather than brand name wares. So manufacturers and wholesalers "extended" themselves to paying in whole or part for advertising at the local level that featured their products. Thus the term "trade extension."

The practice described persists to this day, now called "co-op advertising." It’s just that in an era before mass media, it played a bigger role in the overall merchandising scheme of this and many other industries. It also fostered closer cooperation and interdependence throughout the chain of distribution.

Then as now, there were concerns about encroachment into plumbing and heating markets by outsiders such as hardware chains and mail order houses. Contractors complained about "piratical jobbing houses," i.e., wholesalers selling retail. Trade extension enabled manufacturers and wholesalers to resolve these problems as well as increase sales.

The movement arose in a markedly pro-business environment. This hadn’t always been the case with the American masses. The nation had passed through business eras highlighted by slavery, robber barons, child labor, sweat shops and other outrages that showed the dark side of unfettered capitalism. Beginning with abolition, through the antitrust legislation of the 1880s and continuing to World War I, the federal government was compelled to rein in many of the business world’s abuses.

Then the American business community got caught up in the patriotic fervor of the war effort and sacrificed along with everyone else. This seemed to gain them respect, and, of course, everybody loves a winner. The afterglow of victory unleashed pent-up consumer demand, and people began to sense that business relationships epitomized social harmony. President Calvin Coolidge expressed this in his famous 1925 dictum, "The chief business of the American people is business." In this context, trade extension could be viewed not only as a business strategy, but as a sort of noblesse oblige that enhanced social order.

In the plumbing-heating industry, the trade extension concept quickly expanded beyond advertising. The complaint then, as now, as always, was that the retail link was the weakest. Manufacturers and wholesalers kept hammering away trying to create "merchant plumbers" out of the mechanically-minded trade. Plumbers and the master fitters of steam and hot water heating were acknowledged to be superior craftsmen, but most lacked even rudimentary business skills. Unless you shored up these deficiencies, went the thinking, advertising support would go for naught.

What resulted was a decade-long era of massive, feverish business assistance to contractors, something resembling an intra-industry Marshall Plan. It got underway with establishment of the Trade Extension Bureau (TEB) in 1919.

Education & Service

The group that was to become TEB began meeting as a committee in February 1918. "It was the first time in the history of this industry that all branches of the industry sat around the table to talk about a common cause," one prominent participant later reminisced.War was raging at the time and the government had put a stop to virtually all but war-related construction. In a series of meetings over the next six months the Trade Extension Committee worked on ways to comply with directives from the War Priorities Board, yet still foster business opportunities for contractors. What it came up with was a series of clever trade advertisements exhorting contractors toward renovation work.

"Make NEW Business From OLD Factories ... The Needs of the Nation Include Factory Efficiency ... Sanitation and Bodily Comfort Is More than Ever a National Necessity," read one of the ads, with artwork showing Uncle Sam pointing a plumber toward a smokestack-ridden plant.

Shortly after the ads appeared in print, Germany surrendered. When Armistice Day came in November 1918, the committee was able to hit the ground running with a mission defined as "devoted to educational advancement so that when peace prevails, America will be the most sanitary nation in the world."

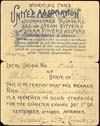

The committee became chartered as the Trade Extension Bureau. It was run by a 22-man board composed of representatives from six manufacturer associations, three regional supply associations and the industry’s two national contractor organizations — the National Association of Master Plumbers (NAMP), forerunner of NAPHCC, and the Heating & Piping Contractors National Association (HPCNA), now MCAA. The contractor groups were assigned three seats each on the board of directors, and TEB’s original by-laws specified that the president of NAMP would automatically serve as chairman.

Selected as staff manager of the Bureau was one of the most innovative movers and shakers in the history of the industry, William J. Woolley, of Evansville, Ind. Known as "the Hoosier genius," Woolley was a successful plumbing and heating contractor and industry activist who revived the moribund Indiana state master plumber organization. Under his guidance, the Indiana Society of Sanitary Engineers began furnishing members, free of charge, uniform estimate sheets, a filing system, collections methodology, uniform contract forms and a system of calculating overhead expenses, among other services. As a result, it began to realize impressive membership gains — 22 percent in 1914, the record shows. What he accomplished at the grass roots level served as a prototype for an ambitious nationwide program of contractor education and services launched by TEB.

The Bureau was officially introduced to the industry in June 1919 at the NAMP Convention in Atlantic City. Based in Woolley’s hometown of Evansville, it was to be funded by contributions from member associations and individual companies. Manufacturers were asked to kick in amounts from $100 to $500. NAMP gave $1,000 and HPCNA $250 towards a first-year funding target of $50,000. In actuality they ended up with $36,918, still a healthy sum in those days. It would be equivalent to more than 10 times as much in today’s dollars.

Some master plumbers got a bit too zealous about the new organization formed to support their interests. Early on, Woolley had to send out a letter asking them not to lean too hard on manufacturers for Bureau funding. On the flip side there was a bit of a turf skirmish, with some state association officials speaking out against TEB, fearing the new organization might usurp their authority over education programs. For the most part, however, the industry was united to a greater degree than ever before.

Sales promotion was TEB’s original mission. That quickly expanded into three separate departments for Accounting, Promotion and General Education. By the time 1919 was over it had compiled service bulletins on calculating overhead and "Short Cuts to Estimating," two topics identified in a TEB survey as the most troublesome to contractors.

In 1920 TEB launched with much hoopla a "National Campaign for Knowledge." The centerpiece was a "Business Efficiency Course," that dealt with accounting, estimating, costing and markup. It was packaged into a series of short, meaty lessons placed at the disposal of local associations.

Later that year TEB trained the first four of its "road men." Drawn from the ranks of experienced industry authors and consultants, these field representatives traveled the country teaching TEB courses and visiting local plumbing-heating businesses. Throughout the decade it lent personal assistance to thousands of small plumbing and heating firms and gave classroom instruction to tens of thousands of individuals.

In Full Roar

Following the war, the nation found itself with a shortage of approximately one million homes. A federal effort launched in 1919, led by Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, exhorted the private sector to “BUILD NOW” and “BUY NOW.” Business began to boom almost everywhere. Following a momentary lull in construction during 1920, the “Roaring Twenties” got underway.The plumbing-heating industry enjoyed the decade about as well as anyone. Between 1919 and 1923 the production of plumbing supplies doubled. The $167 million worth of plumbing produced in 1925, the peak year of the economic boom, was four times the total of 1914. Nonetheless, as of 1922 there were still some 17.5 million homes without baths in the United States, leaving plenty of room for sales growth.

A national survey performed in 1925 and 1926 by the General Federation of Women’s Clubs found that sales of bathtubs increased more than five-fold from 233,940 in 1918 to almost 1.2 million in 1926. By 1926 more than 68 percent of urban dwellings had bathtubs (75 percent in larger cities of more than 50,000 population), and 21 percent of farm homes.

In addition to booming construction, plumbing benefited from a cultural revolution of sorts. Among the ranks of our heroic doughboys were hundreds of thousands of young men from rural America who had never enjoyed indoor plumbing until beckoned by Uncle Sam. They weren’t content with outhouses anymore.

Among other campaigns, TEB incessantly promoted the installation of running water on farms. Also, rural communities were becoming less isolated thanks to regular mail service, telephones and, especially, automobiles. The American Motorists Association reported in 1929 a ratio of one passenger automobile in the Unites States for every 4.5 persons. By comparison, the bathtub ratio at the time was one for every 6.3.

Moreover, during this era regular bathing became transformed in the public mind from something of a frill to a sanitary necessity. The “Bath a Day” campaign originated by the old Domestic Engineering magazine was picked up by TEB and reformulated into “A Bath in Every Home.” A 32-page booklet titled “The Story of the Bath” was distributed to hundreds of thousands of schools, institutions and plumbing customers throughout the land. By mid-decade the effort would be joined by the soap industry.

Similar campaigns were launched to promote radiator heat in homes. This at a time when upwards of 80 percent of American homes were still heated by wood or coal. The campaign acquired a greater urgency during the latter part of the decade when warm air heating technology began to make some headway.

Hoover The Great

Industry progress in the 1920s also was propelled in no small measure by the standardization movement throughout American industry. This was another program headed by Herbert Hoover, whose unfortunate legacy as the President who presided over the Great Depression belies a magnificent career as one of America’s greatest public officials ever.An engineer by training, he was in charge of wartime production during the first world war. There he did an almost unbelievable job converting the nation’s economy from civilian to wartime in about a year and a half, then reversing course just as rapidly and successfully.

Hoover learned from his wartime experience the tremendous amount of waste and inefficiency that resulted from product variations. So as Commerce Secretary in the 1920s, he invented, with voluntary cooperation from business interests, a system of commercial standards in industry after industry. The Commerce Department worked with NAMP and various manufacturer groups to effect changes in plumbing products. In 1920, the plumbing brass sector managed to eliminate more than 12,000 items from their catalogs thanks to standardization.

(Some

prominent members of NAMP objected to the standardization movement, fearing it

would leave the plumber with little to do. Common sense prevailed, and the

association at-large overwhelmingly supported industry efforts to standardize.)

Work in the standards area spawned as

an offshoot, in 1924,

the development of “Recommended Minimum Requirements for Plumbing” in small

buildings, the so-called “Hoover Code.”

It set forth 20 basic principles for DWV design

and installation. Though not a full-fledged code, it served as the

basis for many state and local codes that

followed, making it in effect the first

model plumbing code.

Apprenticeship

About the only thing hampering industry growth during the 1920s was a severe labor shortage. In 1910, the Commerce Department reported 128,000 journeymen plumbers in the United Sates. By 1920, that figure had been reduced to 110,000, and the construction trades had to compete for talent with booming businesses everywhere.Apprenticeship had been a hit and miss affair handled locally ever since the industry coalesced in the 1880s. The United Association, NAMP and HPCNA had dealt with the issue in fits and starts over the years, but always bogged down for reasons still applicable today. Some local unions preferred to keep the supply of labor short to better enhance their bargaining power. There also was jurisdictional bickering and problems over the issue of apprentices vis-a-vis helpers, as well as power struggles for control between labor and management. In steamfitting there was the added complication of what was considered a two-man job.

TEB responded to this industry need as it did to just about every other with an aggressive, wide-ranging program. By 1923, it stuck its nose into apprenticeship recruitment. Its goal was to deliver some 6,000 trained journeymen a year to the industry in 1928, 1929 and 1930, reflecting the standard five-year apprenticeship duration. Towards that end, TEB mounted a publicity blitz promoting the pipe trades to hundreds of schools and civic organizations around the country.

Then as now, actual apprentice training was the responsibility of joint union-management committees, but TEB got involved with producing instructional materials. It also planned to establish an experimental school to test its instruction methods, as well as devise, as “an emergency measure,” a correspondence course for the training of apprenticeship instructors.

By 1927, NAMP reported 7,188 apprentice plumbers enrolled in training programs, compared with less than 3,000 in 1922. However, the dropout rate was high and the industry never came close to achieving TEB’s lofty goal of graduating 6,000 a year by the late-1920s.

Anyway

it became a moot point. The decade began to lose its roar after the economy

peaked in 1925, and labor shortages eased. After the national catastrophe of

Oct. 29, 1929, there were far more journeymen than jobs.

TEB Clout

Nonetheless, its apprenticeship effort serves to illustrate just how influential TEB had become in the industry during the 1 920s. Trade publications of the era hardly ever put out an issue without at least one major article about TEB activities, frequently authored by TEB personnel. Its annual budgets topped $100,000 - well over $1 million a year in today’s money.By 1923, the TEB office in Evansville occupied 6,400 sq. ft. and, according to Woolley, was “crowded to the limit.” As of 1925, TEB was offering a total of 107 different services to plumbing-heating contractors. Staff employment would peak a few years later at 65 employees, including 14 people working out of field offices in 10 different cities coast- to-coast. Here are some other numbers that shed light on its influence:

The Expanded Program

The seeds of the Great Depression were planted in the latter half of the Roaring Twenties. The economy began a steady decline after 1925 but the country kept on spending and speculating. By 1927, some 90 cents of every dollar spent by Americans was going toward consumer purchases, while you needed to spend only 10 cents to buy a dollar’s worth of stock on margin. They were getting hoarse, but consumers still kept trying to roar.The plumbing-heating industry was guilty of the same kind of overreach. With business getting harder to come by in the latter half of the decade, industry leaders, led by former Wisconsin Governor Walter Kohler, began formulating a plan aimed at “inter-industry competition” for consumer dollars.

Kohler counted over 100 industries “organized to get their share of the consumer’s dollar.” These companies spent $10-15 million annually to advertise their wares, “which compete with the plumbing and heating industries,” he said. He oversaw a consumer advertising campaign expansion to 14 field representatives and the creation of a brand new Publicity Department, headed by a young man named Norman J. Radder. Radder would end up spending more than three decades with the Bureau, most of it as its head man before retiring in the 1960s.

Another part of the expanded program was one of the most ambitious local advertising efforts ever ventured by any industry up till then. This was a $70,000 co-op venture with the Plumbing & Heating Development League of Philadelphia. It featured direct mail to some 235,000 homeowners and related newspaper advertising reaching some 850,000 readers a week. Titled “We Keep Faith,” the campaign was intended to boost consumer confidence in plumbing and heating contractors.

Fizzling Out

PHIB had even larger things planned for 1929. TheSaturday Evening Postcampaign was to expand from nine to 13 advertisements, supplemented by ads in prestigious architectural publications. This would be coupled with massive printing of a related booklet promoting the industry to the buying public. Yet even while these plans were being formulated, the Roaring Twenties and this industry’s heyday were simultaneously running out of steam.The Bureau never did meet its $500,000 funding target for 1928. The best available evidence shows they fell about $100,000 short. As business conditions continued to deteriorate leading into 1929, contributions dropped off even more. By mid-year, the national advertising campaign had to be suspended. The field force was reduced from 14 to 4, a separate women’s department was abandoned and headquarters personnel laid off. Creviston resigned in June, saying that the funding cutbacks made it impossible for him to accomplish the ambitious program he was hired to oversee.

Like a three-piece suit worn too long, industry harmony that had prevailed throughout the decade began to fray. Some PHIB leaders even began to question the very premise of “trade extension” that had led to the group’s formation 10 years earlier. One board member argued that collective advertising gave a competitive advantage to the industry laggards who spent no money to promote themselves. People came up with all sorts of excuses to jump off a sinking ship.

The stock market crash of 1929 was the finishing touch. PHIB leaders still bravely forecasted a six-figure budget for 1930, but prosperity never did peek out from behind a corner. Instead the Bureau, and most other American institutions, rapidly got sucked into the black hole of the Great Depression.

The heady $400,000 program of 1928 would dwindle to annual spending of under $10,000 by the mid-1930s. By then only Norman Radder remained on staff. His specialty, generating free publicity, would be the sole affordable function of PHIB.

Postscript

PHIB has carried on performing unglamorous but valuable service to the industry ever since. It remains alive today as the Plumbing-Heating-Cooling Information Bureau, PHCIB, “Cooling” having been added to its name in 1957.Its function ever since the Great Depression has been to generate positive publicity about the industry, which has been accomplished effectively under Radder and all his successors. There was a new surge of advertising and promotion activity following World War II, another era of prosperity, as well as in recent years, when PHCIB once again has emphasized promoting contractors as product merchandisers.

However, the modem era’s budgets and staff pale when compared to the glory days of the Roaring Twenties. It was a unique time in which ambition and wherewithal coincided at a higher plane in this industry than ever before or since. It must have been fun.

This report was compiled from the following sources: