Fresh water is an undeniably valuable and essential natural resource. But are plumbing engineers unintentionally putting building occupants are risk by implementing water conservation guidelines and equipment? What are the unseen consequences of water conservation?

Water facts

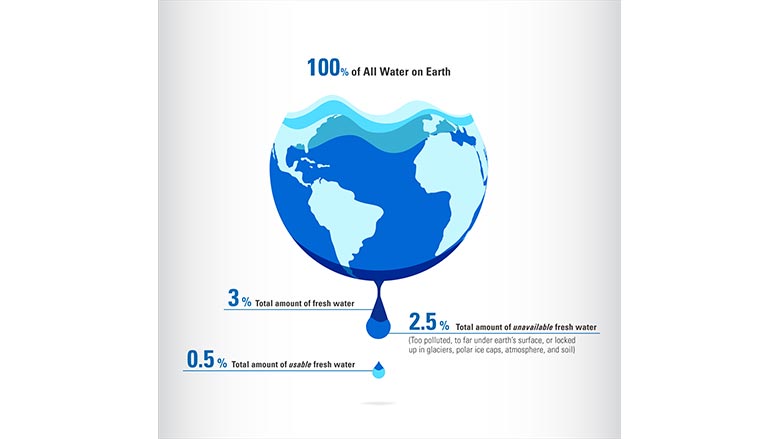

Plumbing engineers are tasked with the responsibility to keep up with the latest water conservation mandates, guidelines and initiatives as well as an unending stream of new products flooding the market designed to reduce water usage. That must be a good thing, right? Who doesn’t want to save a natural resource as precious as fresh water? According to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), of all the water on earth:

- The total amount of fresh water: 3%;

- The total amount of unavailable fresh water: 2.5% (too polluted, too far under earth’s surface or locked up in glaciers, polar ice caps, atmosphere and soil); and

- Total amount of usable fresh water: 0.5%

To put this in perspective, if all the world’s water supply were represented as filling a 26-gallon jug, only about a 1/2 teaspoon would represent our usable supply of freshwater. The good news is this amount is relatively constant and not likely to decrease in the aggregate. The bad news? While this supply is continually collected, purified and distributed in the natural hydrologic (water) cycle of evaporation and precipitation, it may not always be available where it is needed. And even when it is, there are still good reasons for businesses to follow water conservation guidelines. But are conservation and sustainability methods always compatible?

Water conservation efforts

Years of drought have plagued many areas of the country, impacting daily life for individuals and businesses alike. Taking steps to conserve water in these locations is more than good ecological practice, it’s an existential necessity.

For other regions where water is more readily available, there are still incentives to be more hydro-responsible. Building owners, operators and companies are looking for ways to welcome back tenants and employees to post-pandemic office spaces. Creating a safe and healthy work environment is a big part of that equation.

Pursuing evidence-based, third-party verified certification for building improvements, such as the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) LEED rating system, the WELL Health-Safety Rating or Fitwel, can lead to greater tenant confidence and trust, more efficient and cost-effective building systems, reduced water consumption and an overall healthier office environment.

Except when those guidelines contribute to a less-healthy environment.

“Water age” issues

Unfortunately, in a noble quest to conserve water, these standards have inadvertently increased the age of water in many building piping networks. Age of water? Let me explain…

In nature, water flowing from a crisp mountain stream is often viewed as clean and fresh, while its final destination, pooling in a stagnant, algae-filled pond, may be less than appealing. And for good reason — still water is a more welcoming environment for the growth of pathogens. While they still may be present in fast-moving spring, any wilderness survival expert will tell you your odds are much safer drinking from a rapidly running water source.

The same can be said about the water running (or sitting) in your building’s pipes. Water that more constantly moves through a piping network is likely to stay fresh, while water that is stagnant will become more hazardous for building occupants the longer it sits. We call the amount of time sitting idle in the system “water age” and it is becoming a very real term in the plumbing engineering community.

The problem of increased water age is nothing new. Water conservation efforts started in earnest with the U.S. Energy Policy Act of 1992. With bipartisan support, this legislation presented the first national standards requiring water efficiency in new consumer products and dramatically changed how Americans use water. In the intervening years, standards for toilets, showerheads, washing machines and other plumbing fixtures have saved billions of dollars while protecting water resources across the country. The plumbing industry was a big part of this push.

Today, low flow and flush volume fixtures are commonplace. Unfortunately, while one problem is solved another has been created. The new issue is the piping network behind the walls of buildings. The size of the piping, specifically. Plumbing engineers are currently obligated to follow codes to size water supply piping that uses 80-90-year-old data established when plumbing fixtures flowed at considerably higher volumes than they do now.

Increased water age degrades water quality, corrodes piping, increases sediment, and reduces or eliminates primary and secondary disinfectant levels introduced by municipalities in water distribution networks. Fundamentally, this lowers the water quality in the piping network and increases the risk of health concerns to building occupants. The key to maintaining water quality is circulation and consumption in the distribution system. If less water is flowing through pipes, unhealthy chemicals, pathogens or other unwanted components may be present and less diluted, which in turn may necessitate the increased flushing of the distribution system.

The market has begun to introduce flushing protocols into existing buildings and has developed plumbing fixtures with intelligent features that operate if inactive for a given period to keep water moving in building systems. While this is a much-needed practice and move forward in our industry, a lower overall volume of water in building piping networks must be accounted for in making buildings safe — and sustainable — now and into the future.

Sustainability in plumbing engineering

Third-party rating systems noted earlier are not inherently wrong in their quest to conserve building water usage. There are many regions in the United States and beyond where freshwater is at a premium, and using less water is imperative. But we should not, in turn, risk the health and safety of building occupants in the effort to conserve water.

Thankfully, there are tools and methods available to do both. The International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) has released a tool called the Water Demand Calculator which modernizes the calculation method of water supply pipe sizing. According to an IAPMO study:

“(The Water Demand Calculator) works to accurately predict water use patterns in residential (and now commercial) buildings so that water pipes are properly sized, significantly reducing water aging in buildings. The use of the WDC also provides for faster hot water delivery times throughout the hot water systems. As such, it will also save energy, water, and reduce utility bills for the entire life of the plumbing system.”

This tool is included in Appendix M or the 2018 edition of the Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC).

Similar guideline changes are being instituted in city codes across the country. In Chicago, the plumbing code has been revised to increase the total number of water supply fixture units that can be applied to a given pipe size.

Efforts that modernize pipe sizing methods that we see from IAPMO, along with water conservation efforts from organizations such as LEED, marry the idea that water conservation can actually be sustainable and meet the plumbing engineering community’s outcry for a safer, healthier and more sustainable system by the plumbing engineering community.

Water conservation and sustainability — are they compatible?

Absolutely. But it requires care and attention. Today’s efficiency rating standards force engineers to re-think plumbing infrastructure design that encourages both true water savings and healthy, sustainable operations.

Awareness of the challenges and potential problems of legacy piping systems when combined with updated fixtures is the first step in creating healthier standards for occupants. The same is true for designing new facilities — don’t rely on outdated specifications when determining proper flow rates and fixtures. With proper care and planning, there is no need to slap a metaphorical expiration sticker on your client’s water supply.