Of all the topics I’ve covered in my column, strategy is the one to which I keep coming back. Astute readers might be asking at this point, “Why?” Especially when we hear so often that “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” and other axioms that denigrate strategy. Why does Christoph keep on writing about this “outdated” topic more than others?

Even though strategy is not “fashionable” at the moment, the truth is it’s needed more now than ever: eBay, Kodak, Blockbuster, etc. all failed due to poor strategy. Harvard Business Review has found that 95% of employees don’t understand their company’s strategy, nor how they fit in. Gallup found 7 out of 10 employees are struggling this year “post-pandemic.” These things are not unrelated; in fact, they are related because of bad strategy. Bad strategy leads to over-committing to work, poor decisions and to overworking of staff.

Culture is certainly important. A good culture can overcome bad strategy for short periods of time, but that misses the point: What if your strategy and culture were aligned and both were good? The results would likely be… phenomenal. Even better, what if your strategy developed the culture? Shouldn’t some intentional decision and execution be made in regard to strategy? Isn’t culture, in large part, developed by the people of the organization? And aren’t the people in the organization typically recruited and hired? And if they are recruited and hired, what is the process of interviewing them? Is the interview process haphazard or is it intentional? Does the process (and its outcomes) align with the goals of the organization? Does this process align consistently in the strategy of the firm?

Hopefully you can see the picture I am painting — strategy, when done correctly, is not something that is done just once a year. It never ends, because strategy also includes execution — yearly, monthly, daily and hourly. That takes discipline, but also flexibility in knowing when to take the path of least resistance as circumstances change.

It takes a systems approach, meaning someone needs to be responsible for that work. That person could be the CEO at small firms, but as the organization grows and as the pace of business speeds up, the CEO becomes focused on making sure organization is also focused, plans are being executed and ensuring strategic development becomes continuous. When that happens, the CEO needs an executive at hand to share the load. Hence, a CSO — chief strategy officer — role, or even strategy department, is needed as organizations get larger. The very large risk in not having this kind of person or team is to become aimless, as the question “Does this align?” can often be forgotten.

There is another benefit of having a CSO or strategy department — to better react and innovate to a changing business landscape. This concept, emergent strategy,¬ requires someone continually look at medium- to long-term priorities to make sure the organization isn’t losing its way. It also requires the strategic planning process is continually ongoing to ensure the organization pivots intentionally (with full-bore focus) on business opportunities that emerge. Does the company make the intentional decision to go after the new opportunity while saying no to its original goal? What does that look like? What does the business environment seem to be revealing?

Two giants in strategy development said it well:

- “Strategies emerge as people, sometimes acting individually but more often collectively, come to learn about a situation as well as their organization's capabilities of dealing with it. Eventually they converge on patterns of behavior that work,” said Henry Mintzberg, author of “Strategy Safari.”

- “Very often, when a company is trying to implement a deliberate strategy, they’re focused on their [original] goal. On the right and on the left, there are emergent opportunities that they don’t even see because they’re so focused on the original goal. If you’re in a mode of emergent strategy, yes, you have to go after something in a deliberate way. But you have to plan on things to emerge on the right and on the left of that which you may never have thought about before,” said Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School.

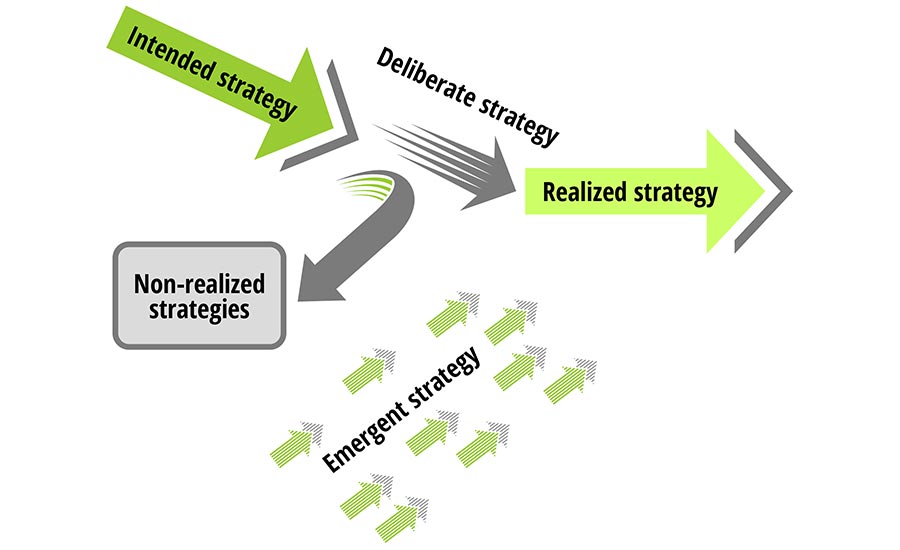

Figure 1:

What you notice is in Figure 1 is an (1) intended/deliberate strategy. There is also (2) flexibility in modifying it based on available opportunities (“the path of least resistance” or the emergent strategy). There are also (2) strategies that are discarded (saying “no”). All of these factors are needed in order for a strategy to be “realized” (i.e. be successful). Who should be constantly thinking about all these factors? The CEO, of course. But this becomes more difficult as an organization gets bigger; this is when hiring someone to help the CEO manage this thought process is necessary, or CEOs risk losing the script.

When the United States entered WWII, there was a massive uphill climb for the U.S. military, having to scale up from 200,000 active duty personnel to more than 16 million soldiers, airman, sailors, and Marines by 1945. The man responsible for this scale up, organization, coordination (often with congress), and collaboration was Gen. George C. Marshall (VMI Class of 1901).

Marshall’s role was Army chief of staff (CoS), but don’t let his title fool you — Marshall was the CSO for the United States. Take a look at the table below, which compares what Marshall did in his role as Army chief of staff to the corporate version of a chief of staff and also the CSO:

Sources:

1. This Is How George Marshall Built The U.S. Army To Win World War II | The National Interest

2. George C. Marshall - Wikipedia

3. Marshall Begins Duties as Acting Army Chief of Staff - George C. Marshall Foundation

4. What Is a Chief of Staff and When Do You Need One? | Bridgespan

5. The Chief Strategy Officer (hbr.org)

Clearly, Marshall could be classified as more of a CSO than a CoS in a corporate sense. Yes, some portions of the CoS role do overlap with both Marshall’s role and the CSO role, but Marshall was the person setting strategy and his vision (CSO), not just managing the process (CoS). He exerted influence to the point of noting that Congress “had begun to trust my judgement” during this scale up.

But in case you don’t believe me that there is still a need for a CSO (or a strategy team), don’t take my word for it; just look at what one of the world’s premier health organizations, Mayo Clinic, is doing: Mayo Clinic has now created a strategy department leadership team headed up by a newly hired CSO. The Strategy team will consist of the following roles:

- Director, strategic initiatives: Leads interdepartmental operations and leads and executes on strategic initiatives;

- Executive director, client services: Works effectively across department to ensure that functional leaders and teams are abreast of important client needs;

- Executive director, strategy intelligence: leads efforts to drive major, strategic decision-making with insights based on analysis of external environment;

- Executive director, strategy planning: Leads the function of strategic planning across the enterprise;

- Executive director, strategy development: Responsible for the formulation of corporate and business unit strategies;

- Executive director, enterprise portfolio management office: Leads the portfolio/program/project management and business analysis;

- Executive director, consulting services: Integrates multiple disciplines to study and optimize processes using a systems approach; and

- Executive director, strategic value: Evaluate performance to make strategic recommendations to leadership.

Reading through the descriptions, the message is clear what this team is all about: Identifying emergent opportunities, focus of resources, cross-department coordination, providing answers to challenging questions and using a systems approach. (Where have you heard that before?) In essence, this team, led by the CSO, will attempt to do for Mayo Clinic in health care what Marshall did for the United States in WWII. But Mayo Clinic is a large organization (more than 10,000 employees), and the U.S. Army numbered in the tens of millions by the end of the war. What does the CSO role look like at smaller companies, such as an engineering firm? I will answer that question in my next column.

LaylaBird/E+ via Getty Images.

Christoph Lohr, P.E., CPD, LEED AP BD+C, is the vice president of strategic initiatives at IAPMO. All views and opinions expressed in this article are his alone. Have some thoughts on this article? Contact Christoph at christoph.lohr@iapmo.org.